Evolution of moist petfood –

A chronicle of opportunities and challenges

By David Primrose, Synergy Petfood

The role of opportunity in the origins of commercially prepared pet food and moist pet food

The domestication of cats and dogs as animals dates back to ancient times with the greatest increase in their acceptance as household pets in the 19th Century. The catalyst for this trend can be linked to three factors: – the Industrial Revolution, the rising status of the middle class and the commercialisation of prepared pet food.

Aligned with this we see the introduction of the first commercial pet food in 1860’s by businessman James Spratt. The opportunity for Spratt’s “Patented Meat Fibrine Dog Cake” reportedly originated from his observation of street dogs eating sailor’s hardtack biscuits in the docks of Liverpool, UK (1)

The birth of canned pet food occurred in 1922, when US businessmen Chappel Brothers saw the opportunity of canning “surplus” horse meat as a source of “lean red meat” for balanced diet food for dogs (2). Whilst no longer widely accepted in pet food in today’s society on the basis that horses are seen nowadays as companion animals, consumption of horsemeat by humans was more widespread in the 1920’s.

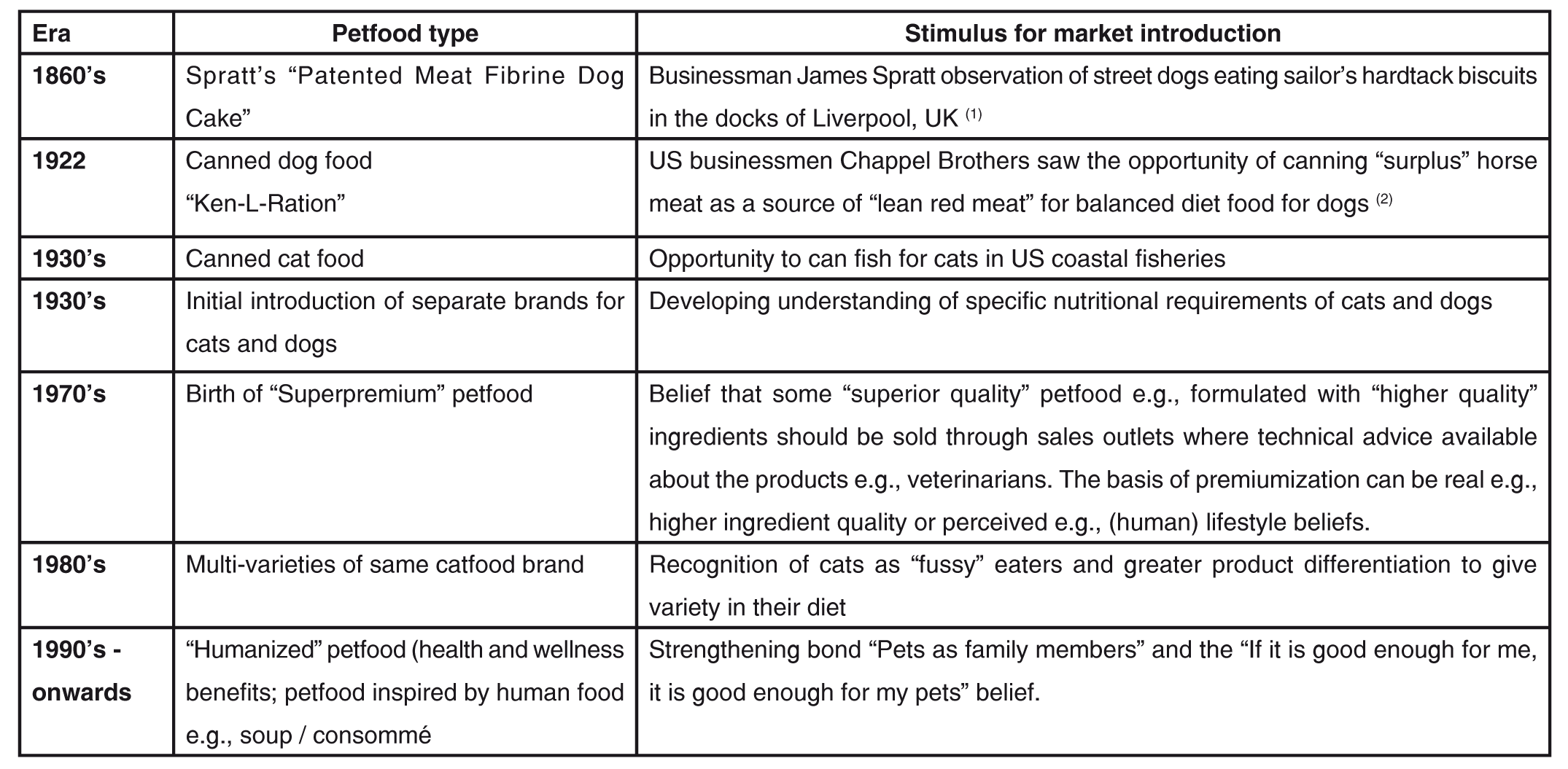

Key points in the history of pet food and the stimulus for commercialisation and market growth are summarised in Table 1.

In recent years, development of innovative new products in the petfood evolutionary process, often arises from a combination of pet owner demand for “premiumization” and “humanization”. For example, premium / super premium wet pet food formats that take their inspiration from human foods e.g., wet pet food with a liquid centre looks similar in appearance to “melt-in-the-middle” chocolate souffles; soup for cats that looks like consommé.

The concept of “Premiumization” first originated in human consumer goods e.g., alcohol where consumers wanted products that “provide greater benefits and characteristics” compared to “standard” products. This impression of “premium” quality can be real or perceived in the mind of the consumer. In the context of pet food, this might mean parameters like: –

- GMO free ingredients and products

- Marketing terms e.g., “holistic” create an impression of “greater benefits and characteristics” achieved through a combination of factors e.g., natural raw materials, additive free, greater transparency in ingredient inclusion etc.

- Higher protein content compared to “standard” products.

It should also be noted that pet food “humanisation” extends beyond the actual pet food product and includes expectations on petfood manufacturing business philosophy and product beliefs, for example: –

- Use of human food industry approaches to quality and food safety management systems, giving rise to the “If it’s good enough for me, it’s good enough for my pet” belief.

- Lifestyle choices and beliefs that match their own lifestyle choices e.g., “natural”, sustainable etc.

- Extension of human lifestyle choices are also stimulating petfood market growth e.g., the growth of the vegan pet food market.

In recent years, it is clearly evident that evolution of wet pet food has been closely linked to trends in the human food sector. The question is where next for wet pet food evolution?

Will veganism and flexitarianism drive the rebirth of meat analogues in wet petfood?

For many reasons, humans are turning more to the purchase and consumption of meat analogues, as a means of reducing meat consumption. The question is “What is a meat analogue and why is there growing interest in them”?

There are many definitions of meat analogue and one of the most useful is from Dekkers, Boom and van der Goot(3) : –

“Meat analogues are products that can replace meat in its functionality, being similar in product properties/ sensory attributes, and that can also be prepared by consumers as if they were meat.”

Typically, meat analogues for human consumption are manufactured from sustainable plant-based proteins giving rise to many of their perceived benefits including: – animal welfare, greenhouse gas emissions / carbon footprint and health benefits compared to meat consumption. These factors are contributory to increased interest in veganism and a “flexitarian” approach to eating (consumption of a varied diet based on meat eating and plant-based protein eating on different days, with the overall effect of reduced meat consumption).

Meat analogues are not new and date back to Classical and Medieval times where seitan (based on wheat gluten) and tofu (based on soya bean) were examples. Although these are still used, in the context of human food, a more widely known example of plant-based meat analogues is “Texturized Vegetable Protein” (TVP). Traditionally made using low moisture extrusion, and based on soya or wheat gluten, TVP is available in many forms that mimic either pieces of meat, minced meat, or fibrous steak-like meat pieces. TVP has also been used in wet petfood in the 1980 – 1990’s, where its fibrous structure was designed to mimic beef or chicken steak.

In addition to TVP, the concept of using other meat analogues in wet petfood is not a recent innovation. The petfood industry has seen many other meat analogue technologies developed and patented over the last 60 years, some of which have been implemented on a commercial scale. There are many factors that affect commercialisation and these include cost and consumer acceptance / perception of meat analogues i.e., are they affordable and do they look like “real” meat. Examples used commercially include: –

- Heat-set emulsion-based meat analogues – this is the basis of both human food sausage manufacture and the widely implemented “Oven Formed Meat” technology used to heat-set meat chunks for use in chunks-in-gravy and chunks-in-jelly products

- Gelled meat analogues – Examples include those based on sodium alginate gelation and also konjac glucomannan gelation. Both technologies have also been used in human food to make imitation glace cherries, pimento pieces and konjac noodles

Development of “next generation” meat analogues is the subject of extensive science and technology research. Compared to the pioneering early developments, “next generation” meat analogues are designed to better satisfy consumer needs especially cost and sensory appeal (taste, smell, texture). In other words, they must overcome the barriers of cost and authenticity compared to “real” meat, associated with historical forms of meat analogue. With these aims in mind many new technologies are being developed including high-moisture extrusion and shear cell technology(3).

Challenges and opportunities in use of “next generation” meat analogues in wet petfood.

The concept of plant-based / vegan petfood is not new and in recent years we have seen both dry and wet complete petfoods enter the marketplace. If we look at vegan wet petfood, typically the structure often appears similar to “all meat” pate or hybrid meat / cereal products that have been on the market for many years. For product differentiation, some include TVP pieces in the product along with other inclusions like fruit or vegetables.

In recent years, the petfood industry has seen many new start-up’s enter the market. These start-up’s often utilise different business models compared to “traditional” petfood manufacturers. One factor is “disruptive innovation” and this factor could offer a route to market for many of the emerging “next generation” meat analogue technologies once these are ready for commercialisation.

Another factor that opens opportunities for plant-based meat analogues (PBMA) in wet petfood is the supply chain vulnerabilities evident during the recent Covid-19 pandemic. Many experts believe that PBMA offer opportunities to reduce meat supply chain vulnerabilities evident during the pandemic (4) that saw a surge in market demand for plant-protein foods. This might result in greater interest in PBMA in wet petfood as pet owners mirror their own buying patterns in what they buy for their pets.

Research by many different groups, for example Dodd et al (2019)(5), indicate that more pet owners would be willing to buy vegan petfood but the biggest barrier to overcome is convincing evidence on the (long-term) nutritional adequacy of these products. This is a key research need if we are to see greater acceptance of plant-based petfood.

The petfood industry has thrived on converting opportunities into reality and enjoyed market growth as a result. However, in doing so the industry has had to overcome many challenges.

With the realisation that PBMA or maybe “hybrid” meat analogues based on plant and meat ingredients offer many opportunities there is no escaping the fact that challenges exist. However, if the industry adopts a collaborative approach, involving all stakeholders including pet owners, veterinarians, nutritionists, food scientists and food technologists then there is greater probability that these challenges can be overcome.

References

1) One Nation Under Dog,. M. Schaffer, 2009, Macmillan, 9780805091465

2) Philip. L. Chappell 1923 – Ken-L-Ration viewed online on 4th May 2021 at https://history.rockfordpubliclibrary.org/localhistory/?p=36608

3) Birgit L. Dekkers, Remko M. Boom, Atze Jan van der Goot, Structuring processes for meat analogues, Trends in Food Science & Technology, Volume 81, 2018, Pages 25-36.

4) Protein and produce in a post-COVID-19 world, viewed online on 12th May 2021 at https://www.mintel.com/blog/food-market-news/protein-and-produce-in-a-post-covid-19-world

5) Dodd SAS, Cave NJ, Adolphe JL, Shoveller AK, Verbrugghe A (2019) Plant-based (vegan) diets for pets: A survey of pet owner attitudes and feeding practices. PLoS ONE 14(1): e0210806.

Other Topics

Contact

Phone

01994 240002

Address

Plas y Coed, Velfrey Road, Whitland SA34 0RA